concept to operation

To transform development of complex systems, market-leading companies adopt Model-Based Design by systematically using models throughout the entire process.

- Use a virtual model to simulate and test your system early and often

- Validate your design with physical models, Hardware-in-the-Loop testing, and rapid prototyping

- Generate production-quality C, C++, CUDA, PLC, Verilog, and VHDL code and deploy directly to your embedded system

- Maintain a digital thread with traceability through requirements, system architecture, component design, code and tests

- Extend models to systems in operation to perform predictive maintenance and fault analysis

No Downloads or Installations

Simulink Online provides access to Simulink from any standard web browser wherever you have internet access. Simply sign in to MATLAB Online and either start Simulink or open an existing Simulink model. Simulink Online is ideal for teaching, learning, and convenient, lightweight access.

Simulink Is for Simulation

Design and simulate your system before moving to hardware

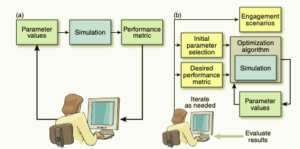

Explore a wide design space and test your systems early with multidomain modeling and simulation.

- Quickly evaluate multiple design ideas in one multidomain simulation environment

- Simulate large-scale system models with reusable components and libraries including specialized, third-party modeling tools

- Deploy simulation models for desktop, real-time, and Hardware-in-the-Loop testing

- Run large simulations on multicore desktops, clusters, and the cloud

Developing a Control Algorithm and Simulation for Thrust Vector Controlled Rockets

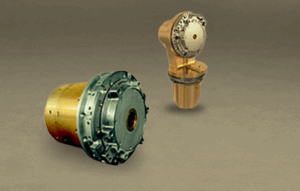

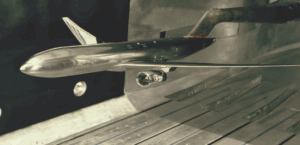

Currently, there are over 10,000 companies in space technology development with a combined value of over $4 trillion (Koetsier, 2021) dedicated to advancing technologies in navigation, tourism, national security, communication, and outer space research. This expansive growth prompts the need for new suborbital and orbital-class vehicles to transport these technologies into outer space. Although these vehicles, the majority being rockets, present multiple challenges, one of the biggest obstacles is developing a navigation and control system to guide them. A majority of these spacecraft use a technique called thrust vector control (TVC) (Figure 1). By angling or vectoring the direction of the thrusting component, the rocket has control over position and orientation, even in a non-atmospheric environment (Hall, 2021). Engineers have designed and implemented gimbals into the rocket engines to allow for this technique across a variety of different rockets, but the software to control these gimbals and the rockets becomes very complicated because of the high speeds, large masses, and precision required from spacecraft. Furthermore, methods to tune these control algorithms also become very complex due to the high cost and the large number of variables involved in a rocket flight. Although a majority of rockets use the same technique as TVC for active control, the control system design and tuning present many challenges.

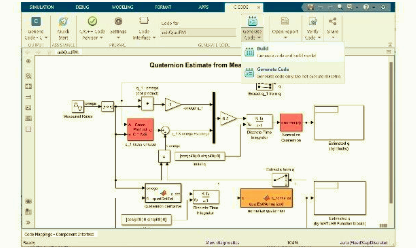

Where u(t) is the output, K p , Ki , and Kd are the three gains, e(t) is the error value and the input to the controller, and ∆t is the change in time. There are three terms to this equation: the proportional, integral, and derivative of the error value e(t), which are scaled using the adjustable gains K p , Ki , and Kd. The proportional, integral, and derivative components allow for control over oscillations, overshoot, and small errors. This simplicity allows for use on lower-powered flight controllers, but the three components work together to produce a very robust, efficient, and versatile control system. On a rocket, this method can be easily integrated. We can have three PID controllers, one for each axis to control orientation. The error, which is inputted into the controller, is equal to the setpoint subtracted from the current orientation. The setpoint is adjustable based on the desired angle. After performing the proportional, integral, and derivative components, we can then command these angles to the gimbal, or thrust vector control mount (Figure 2). 2 METHODS 2.1 Real-World Model To validate that the control system and simulation worked properly, we designed a model rocket and a TVC gimbal in computer-aided design, CAD, and 3D-printed components to replicate a real-life rocket (Figure 3). The rocket itself was printed in PLA and supported by four carbon fiber rods. Parachutes that were stored in the upper body were deployed using a small pyrotechnic charge ignited by a load driver aboard the flight computer. The thrust vector control mount was a two-axis (Figure 4) gimbal that was designed to vector the rocket motor using two servo motors that were controlled by the flight computer. The gear ratio of the motors and the mount was 2:1, which allowed for more accuracy and less error within the mount, and the mount had a range of +/- 5 degrees on both axes.